Toxicology and Drug Safety Issues: A Review Article

Abstract

Background

Research and drug development industries have multiphase drug screening procedures, which can be debated. As a result, harmful products may still reach for public health service delivery due to vulnerabilities in the process.

Main body

A wide range of test compounds have delayed manifestation of undesired effect on the study subject, with the time to undesired effects after acute exposure being weeks and months. Acute toxicology in a preclinical trial also has limited clinical value as its lethal dose is the endpoint for a conclusion, and death sometimes occurs after a scheduled period of acute toxicology. Countless resources are wasted, and numerous new drugs are introduced into the pharmaceutical market with assumed safety analysis every year due to vulnerable multi-procedures in preclinical trials. The principal use of collected data from a preclinical trial is to support regulatory categorization and harmful labelling decisions. However, the data can also be used to derive safe use threshold levels, which may lead to the use of unsafe material. The criteria for classification and labelling also differ among countries, sometimes among authorities within the same country. The fundamental concept of toxicology states that ‘all chemical substances are potential poisons depending on the amount and duration of exposure. However, the toxic property of a test compound cannot be created or eliminated by simply the amount administered to study animals.

Conclusion

All xenobiotics are poisons at any amount with different severity that can be calculated using biological parameters.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Yilkal

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Citation:

Introduction

A preclinical trial is a basic step in the developing of unknown drugs into pharmaceutical products. Multiple testing procedures are involved in the practice. The first step of a preclinical trial is to determine the safety margin after administering of a single dose of test drug through a chosen route. This safety assessment is usually completed within a 24 hour period 1, 2, 3. Acute toxicity studies are usually conducted to support the development of new drugs or medicine, with the death of study subjects used as an end point for drawing conclusions 2, 3. However, using the lethal effect as an end point makes acute toxicity study less valuable in safety regulatory measures 2, 3. There is no specific minimum lethal dose and maximum non-lethal dose for every test chemical substance that could be evident within 24 hours 1. Different doses have different timeframes for causing significant pharmacological effect in treated subjects 1, 2, 3. The range of doses that can cause a lethal effect to treated study animals also varies extensively due to factors such as strain, age and sex of the study animals as well as route of drug administration 4. According to existing guidelines, the aim of acute toxicity study is to identify the dose which causes major adverse effects and to estimate a minimum lethal dose within 24 hours, although this is not scientifically well grounded 5. The limited value of acute toxicity studies in terms of preclinical and human safety assessment is attributed to the adverse effects of significant test compounds that manifest after 24 and 48 hours of administration to a study subject 2.There is no clinical pathology, immunology or other clinical measures conducted in acute toxicity studies to validate the data with adequate scientific background 2, 3. This has raised controversy on both ethical and scientific grounds regarding preclinical studies as they necessitate more time and resources for the assessment of lethal endpoint studies with limited scientific toxicity analyses.

The death of study animals can occur due to a test compound causing loss of bodyweight (wasting syndrome) and appetite suppression, even if it does not directly cause death during preclinical trials 5. The impact of a test compound on biological processes is considered toxic if it interferes with the normal functioning of the study animals 2, 3. The administered substance may have adverse effects at the cellular or organismal levels, depending on the dosage, and may cause death at different time intervals after dosing 1. The amount of a dose, therefore, determines the magnitude of a biological response which consequently determines the lifespan of study animals 2, 3. Death typically occurs when the nonviable part of the biological organ or system surpasses the viable part in the diseased organism 2, 3. Death is, therefore, used to describe an organism that has lost bio-physiological interaction with its environment, where it has existed for years and decades 2, 3. The levels of doses prepared from a test compound may manifest its toxic effect on study animals with varying magnitude at different time intervals depending on the amount of dose administered into the biological system. If the higher dose is lethal to the study subject, then the lower dose is most likely to have undesired effect in the long run 2, 3. Previous studies conducted in 2011 and 2019 have shown that there is no scientific ground to categorise the different levels of doses of a test compound as a safe dose (ED50) and lethal dose (LD50) to the treated laboratory animals within the period of the experiment 1, 3. The lower dose could not be considered safe when the higher dose is lethal 1, 3. It is likely a waste of time and resources to categorise a single test substance as an effective dose (ED50) and lethal dose (LD50) and proceed to the next phase of preclinical trials with inadequately validated data 1. Countlessresources are being wasted every year and harmful pharmaceutical products are infiltrating the market for consumption due to unrealistic procedures in preclinical trials, where the lethal dose is the endpoint for drawing conclusions 1. A dose that is highly toxic to one species may not have the same pharmacological effect on another species 2, 3. Furthermore, a dose of a test compound may not even have the same pharmacological effect on the same species of animal due to differences in the strength of natural immunity, and biological sensitivity 6.

There are significant developments in the discoveries of therapeutic agents every year but the process of translating these discoveries into improved health outcomes has been disappointingly slow 7.while we have made progress in controlling infectious diseases, we have not been as successful in controlling non-communicable diseases such as cancer and diabetes. In some third world communities, traditional medicines are still being used to prevent and treat new and re-emerging diseases, often without proper clinical analysis. This may be contributing to the high incidence of cancer worldwide 1. A study from 2011 found that test extracts from a traditional medicinal plant called Aristolochia elegans mast caused severe damage to the kidneys and livers of treated Balb c mice, as well as stomach hemorrhages in some cases, indicating its carcinogenic properties 1. Different members of local communities have been using this herbal product with different dosage forms to combat malaria parasites 1. The study concluded that individuals using this herbal preparation are at a high risk of getting stomach cancer as well as renal and hepatic diseases.

Over the past several years, there have been significant changes in the strategy for preclinical trials. The aim is to ensure that early toxicological data can help in making decisions on the best compounds to develop as effective human medicines 8, 9. However, there is still an urgent need to establish realistic research guidelines with a comprehensive biological approach to accelerate the development of safe therapeutic agents with minimum cost and time. The high rate of unsuccessful clinical trials in developing safe therapeutic agents is still frustrating as it involves a significant amount of money is being spent on drug discovery and development that doesn’t yield results. It is critical to implement a validated research system with a comprehensive biological approach to better predict potential therapeutic agents at the earliest stage of preclinical trials. Regular clinical and immunological evaluations need to be conducted for an adequate duration during preclinical trials to ensure public health safety.

Construction and content

The preclinical data shows the relationship between the dose of various test chemicals and their biological responses. The data was selected based on clinical and immunological parameters from two studies published in 2011 and 2019. The selected data was analyzed manually using Microsoft Word 2013 and a Smartphone calculator to further explore technical and biological content. The information has been organized into categories and sub-categories, which will be described in the next sections. The compilation of preclinical data from different sources aims to define research guidelines in drug discovery and development.

Utility and discussion

The previous studies conducted in 2011 and 2019 have revealed that the dose has no role to avoid the toxicity of a test chemical but rather it limits the magnitude of pharmacological effect. This determines the period at which a gross biological response can manifest on treated study animals 10.The higher the dose of a test chemical, the shorter the length of time at which signs of undesired biological effects are manifested on exposed study animals. The toxic property of a test compound is diverse, and an integrated biological approach must be considered to analyze its toxicity in a harmonized manner, thereby avoiding unnecessary wastage of time and resources 10. This article uses selected and analyzed preclinical data from different biological perspectives to outline and discuss the crucial steps in preclinical trials which is described as follows:

Identity and chemical structure, physical and chemical properties

It is important to do the right thing at the right time to achieve a desired goal easily. There are necessary steps in preclinical trials that should be followed to avoid wasting time and resources. The toxic property of a test compound is a result of interactions between its molecules with their receptor types during metabolism, where we cannot avoid it by limiting the amount that has to be administered to a study subject. It is important to have information about the identity and chemical structure, physical and chemical properties and the result of any other toxicity studies before conducting a preclinical trial of a test compound 9. This information is important to make a preliminary decision on whether a test compound is relevant for the development of a safe therapeutic agent. This preliminary information is also helpful in choosing the appropriate level of doses for the experiment. As a rule, the different levels of doses need to be determined, including the lowest and the highest possible dose shortly before testing.

Recruitment and sampling of study animals

The second activity in the drug trial involves recruiting of preferred study animals for a preclinical trial and keeping them in a laboratory environment that is friendly to animals. This environment should have a normal sequence of dark and light cycles. Previous studies in 2011 and 2019 indicated that there is no need to sample more than two mice for each dose. It was also found that multiphase drug screening procedures in preclinical trials lead to unnecessary wastage of time and resources. All preclinical phases could be evaluated in a single drug screening procedure. Additionally, studies conducted in 2011 and 2019 showed that there is no need to sample different species of study animals for the experiment because the toxicity of any test compound can even vary within the same species of animals depending on the biological sensitivity and strength of natural immunity 2, 3. After grouping in cages based on experimental protocols and acclimatising in the new environment for a minimum of five days, the biological conditions specifically the bodyweight and immune strength of each sampled animals need to be evaluated 3 days before the administration of prepared doses for a comparison after dosing as shown in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively.

Table 1. Body weight of Balb c mice which was taken three days before and five days after treatment| Test chemicals | Doses tested | Weight 3 days before dosing | Weight 5 days after dosing |

| Dichlorvos | 10 mg/kg | 15.13 g | 13.37 g |

| 50 mg/kg | 17.63 g | 14.72 g | |

| 90 mg/kg | 16.42 g | X | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 mg/kg | 30.41g | 26.58 g |

| 50 mg/kg | 27.12 g | 23.37 g | |

| 90 mg/kg | 26.84 g | X | |

| Cypermethrin | 10 mg/kg | 28.42 g | 23.58 g |

| 50 mg/kg | 30.98 g | X | |

| 90 mg/kg | 28.24 g | X |

| Test drugs | Tested doses | Quantitative immunoassay 3 days before dosing as reference test | Quantitative immunoassay 4 hours after dosing for comparison | Δ Ig serum conc. | ||

| IgG | IgM | IgG | IgM | Δ Ig | ||

| Dichlorvos | 10 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 70 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 90 mg/L | +20 mg/L |

| 50 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 70 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 80 mg/L | +10 mg/L | |

| 90mg/kg | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 90 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 120 mg/L | +30 mg/L |

| 50 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 50 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 70 mg/L | +20 mg/L | |

| 90mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 90 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 80 mg/L | -10 mg/L | |

| Cypermethrin | 10mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 70 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 90 mg/L | +20 mg/L |

| 50 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 80 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 70 mg/L | -10 mg/L | |

| 90 mg/kg | <1100 mg/L | 80 mg/L | <1100 mg/L | 50 mg/L | -30 mg/L | |

Testing procedure

The third activity in a preclinical trial of a test compound involves preparing different dose levels shortly before administering them to the study animals using a preferable route of drug administration. The time at which a test compound is administered to the biological system need to be recorded in notebook as shown in Table 3. The treated study animals should be monitored for any sign of toxicity while being fed conventional animal feeds and having unrestricted access to drinking water throughout the experiment 9. An observational investigation should be carried out at least for two hours three times a day (immediately after dosing, 4 and 10 hours after dosing). The time when signs of toxicity manifest on treated study animals i.e. slow activity, suppressed appetite, tearing, salvation, and so on need to be recorded in a notebook as shown in Table 3 and Table 4. The strength of immune response to the test compound and bodyweight of treated study animals need to be evaluated at least once every five days with having the first immunoglobulins evaluation at four hour after dosing during the period of a preclinical trial as shown in Table 2 and Table 1 respectively 2. The collected data should be processed and expressed as quantitative biological responses such as toxic severity and toxic reaction rate of each administered doses to a study animal in order to determine the clinical fate of tested chemical (Table 5 and Table 6). Quantitative biological responses as toxic severity and toxic reaction rate of an administered dose of a test compound can be determined using the following mathematical formulas, which are explained in details in section 3.5 A and B respectively.

Table 3. The period at which adverse effect significantly manifested on study animals treated with test chemicals orally| Test Drugs | Doses tested | № of Mice | Weight in gm | Time at which test chemicals administered | Time at which signs of adverse effects manifested | Duration |

| Dichlorvos | 10 mg/kg | 1 | 15.13 | 10:22 | 11:22 | 1 hour |

| 50 mg/kg | 1 | 17.63 | 10:23 | 10:53 | 30 minutes | |

| 90 mg/kg | 1 | 16.42 | 10:24 | 10:39 | 15 minutes | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 mg/kg | 1 | 30.41 | 10:28 | 13:00 | 2:30 hours |

| 50 mg/kg | 1 | 27.12 | 10:29 | 12:00 | 1:30 hours | |

| 90 mg/kg | 1 | 26.84 | 10:30 | 11:00 | 30 minutes | |

| Cypermethrin | 10 mg/kg | 1 | 28.42 | 10:32 | 10:55 | 23 minutes |

| 50 mg/kg | 1 | 30.98 | 10:33 | 10:45 | 12 minutes | |

| 90 mg/kg | 1 | 28.24 | 10:36 | 10:45 | 9 minutes |

| Dose in mg/kg | 500 & 1000 | 2000 & 3000 | 4000 & 5000 | Distilled H₂O (0.5 ml) | Cooking oil (0.5 ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of treated mice | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| Adverse effect within 24 hrs | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Within 48 hrs | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Within 72 hrs | Nil | Nil | Depressed appetite | Nil | Nil |

| Within 96 hrs | Nil | Depressed appetite | 2 mice died | Nil | Nil |

| Within 120 hrs | Nil | 1 mouse died | 2 mice died | Nil | Nil |

| Within 144 hrs | Depressed appetite | 3 mice died | 4 mice died | Nil | Nil |

| Within 168 hrs | 2 mice died | 4 mice died | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Within 192 hrs | 2 mice died | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Within 216 hrs | 4 mice died | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Test drugs | Doses tested | Toxic severity (s) in %/sec |

| Dichlorvos | 10 mg/kg | -131.5 |

| 50 mg/kg | -56.2 | |

| 90 mg/kg | X | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 mg/kg | -98.3 |

| 50 mg/kg | -73.4 | |

| 90 mg/kg | 37.3 | |

| Cypermethrin | 10 mg/kg | -70.0 |

| 50 mg/kg | 32.3 | |

| 90 mg/kg | 106.2 |

| Test drugs | Doses tested | Approximate length of time undesired effects significantly manifested | Toxic reaction rate (r) in mg/Sec |

| Dichlorvos | 10 mg/kg | 60 minutes | -19.9 |

| 50 mg/kg | 30 minutes | -9.9 | |

| 90 mg/kg | 15 minutes | X | |

| Chlorpyrifos | 10 mg/kg | 2:30 hours | -29.9 |

| 50 mg/kg | 1:30 hours | -19.9 | |

| 90 mg/kg | 30 minutes | 10.0 | |

| Cypermethrin | 10 mg/kg | 25 minutes | -19.9 |

| 50 mg/kg | 12 minutes | 10.0 | |

| 90 mg/kg | 9 minute | 30.0 |

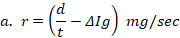

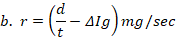

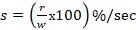

Formula 1→ %/sec and formula 2→

%/sec and formula 2→  mg/sec , where s is toxic severity, r is toxic reaction rate, m is the body weight of a study animal, d is the administered dose, t is the time at which signs of toxicity manifested in treated study animals, and is the change in the concentration of serum immunoglobulin after dosing. Three test chemicals at different dose levels (10, 50, and 90) mg/kg were administered to nine laboratory animals (one mouse for each dose) via the oral route and the animals were monitored for possible signs of toxicity for five days. The preclinical data has been extracted from exposed study animals and recorded in a note book as shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5.

mg/sec , where s is toxic severity, r is toxic reaction rate, m is the body weight of a study animal, d is the administered dose, t is the time at which signs of toxicity manifested in treated study animals, and is the change in the concentration of serum immunoglobulin after dosing. Three test chemicals at different dose levels (10, 50, and 90) mg/kg were administered to nine laboratory animals (one mouse for each dose) via the oral route and the animals were monitored for possible signs of toxicity for five days. The preclinical data has been extracted from exposed study animals and recorded in a note book as shown in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5.

X Represents laboratory Balb c mice which were died earlier than two days after dosing

X in Table 1, Table 4, and Table 5 represents sampled study animals which died earlier than the time for data collection.

Immunoassay after dosing

The immune system is usually activated by biological molecules called immunoglobulins to protect the body from pathogens and harmful molecules. These immunoglobulins work as cell surface receptors for antigens, allowing cell signaling and activation. They also function as effector molecules by binding to and neutralizing invading antigens in the body. Immunoassays are commonly used to assess the normality and functionality of the immune system, as it is the ultimate indicator of an organism's well-being. An abnormal immune response may indicate either elevated or suppressed concentrations of immunoglobulins in the blood serum.

When harmful molecules enter the body, they can disrupt normal biological mechanisms, leading to an adverse immune response. The impact of these molecules can either elevate or suppress the immune response, depending on their properties. Chemical substances that elevate the immune response in treated study animals are likely to be inflammatory drugs, which can result in inflammatory diseases. Inflammation is a painful reaction caused by the interaction between the molecules of a harmful chemical and a biological component, potentially causing damage to a biological system. Pain, in turn, is a complex physiological phenomenon resulting from the adverse chemical reaction against the integrity of biological tissue. These types of drugs are mostly cytotoxic and carry a high risk of causing adverse reactions within an organism's biological system.

The lower doses of the three test chemicals mentioned in Table 2 caused a disproportionate increase in the immune response during the first 4 hours after dosing, while the higher dose caused a disproportionate suppression of the immune response in treated Balb c mice, as shown by drug B in Figure 1. This might indicate that as the inflammatory action of a drug increases, it disrupts the normal physiological mechanism, affecting the metabolic system of an exposed organism and ultimately impairing the immune response, as these two systems are directly interdependent. This category of drugs usually results in significant biological responses shortly after dosing (Table 3).

The second category of chemical substances includes drugs that directly suppress the immune response and are harmful to the metabolic system of an organism. These drugs have characteristics such as depressed appetite and decreased activity in treated study animals, as shown in Table 41. They are further classified as mutagens and carcinogens, with most of them being genotoxic and take a long time to show their biological effects after dosing 18. They disrupt the normal function of the genome, which affects the body's bio-physiological network and leads to abnormal physiological activity, ultimately weakening the immune response, as depicted in Figure 1, drug A. These drugs often exhibit silent undesired biological mechanisms that may result in hereditary or nonhereditary diseases 19. If they damage germ cells and cause hereditary disorders, they can spread in the population through reproduction, with their incidence increasing as the population grows 20. Today, there are thousands and millions of anomalies related to genetic disorders with unknown causes.

The administered test chemical could affect the metabolic system in various ways, ultimately impacting the immune response. It may be directly toxic to cellular metabolism or neurotoxic, disrupting normal physiological activity and impacting the metabolic and immune systems of an organism. In general, any abnormal bio-physiological mechanism within biological systems will manifest as an undesired effect that elevates or suppresses the immune response (Figure 1). The immune response is a complex biological mechanism that acts to protect the biological system of an organism exposed to etiologic agents such as the noxious chemicals and pathogens. The three test chemicals mentioned significantly suppressed the immune response as the administered doses increased from 10 to 90 mg/kg body weight (Table 2). This implies that the test chemicals are not biological friendly for consideration in the development of pharmaceutical or nutraceutical products. However, an immunoassay should be conducted for an adequate length of time to validate the data for a conclusion. Since drawing blood samples for immunoassay daily could affect the biological condition of study animals, it is preferable to do it at least once every five days during the preclinical trial period.

Data interpreting

In preclinical trials, interpreting data without detailed information about the dose-biological response relationship and sufficient time for investigation often leads to failure. It's important to note that a dose does not change the chemical property of a test compound administered to study animals, but it does change the magnitude of the pharmacological effect, which in turn determines the time it takes for gross biological responses to manifest in the treated animals. Different levels of doses prepared from the same test chemical and administered to study animals resulted in undesired biological responses at different times after oral dosing. The dose does not serve to avoid toxicity but instead determines the magnitude of a biological response, which then influences the lifespan of exposed animals. To assess the toxic severity and toxic reaction rate of a test chemical, the gross biological responses against each administered dose need to be computed as shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

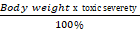

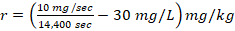

The toxic severity of a dose

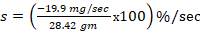

The toxic severity refers to the magnitude of biological harm or injury caused by the administered dose of a test compound which is expressed in percent per second (%/sec). It represents the approximate proportion of biological harm that has been manifested as gross biological response on exposed study animals. It could be expressed quantitatively using an integrated biological approach with the mathematical equation mentioned in formula 1 earlier. The toxic severity of the three test chemicals administered to lab Balb c mice at a dose of 10 mg/kg shown in Table 5 was computed at four hour after dosing as follows:

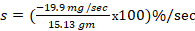

1. The toxic severity of a dose at 10 mg/kg prepared from Dichlorvos pesticide:

%/sec,

%/sec,  ,

,

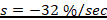

2. The toxic severity of a dose at 10 mg/kg prepared from Chlorpyrifos pesticide:

%/sec,

%/sec,  ,

,

3.The toxic severity of a dose at 10 mg/kg prepared from Cypermethrin pesticide: ,

,  ,

,

The level of toxicity from a dose made with the three test chemicals and given to study animals at 10 mg/kg body weight was found to be less than zero based on the calculations above. This suggests that the dose of the three chemicals at 10 mg/kg caused negligible adverse biological response at the organismal level, possibly due to boosting the immune response, as shown in Table 2. However, this does not prove that the tested chemicals are safe at the cellular level 2, 3. An increase in the immune response could be due to the inflammatory or irritating action of the test chemicals, indicating that they may not be safe at the cellular level. The severity of toxicity was not significantly apparent at the organismal level during the first four hours after being orally administered to Balb c mice, likely due to an increase in the immune response. A substantial adverse biological effect of lower doses might become apparent in the long term within the lifespan of exposed study animals. To better validate the safety of the test chemical at 10 mg/kg at the cellular level, multiple immunoassays should be conducted for at least 15 days (once every five days) after dosing. However, the toxicity of a dose at 90 mg/kg prepared from the three test chemicals was significantly apparent in gross biological response during the first four hours after oral dosing, as calculated below:

1. The toxic severity of a dose at 90 mg/kg prepared from Chlorpyrifos pesticide:

%/sec

%/sec

%/sec

%/sec

37.3 %/sec

37.3 %/sec

2. The toxic severity of a dose at 90 mg/kg prepared from Cypermethrin pesticide:

%/sec

%/sec

%/sec

%/sec

106 %/sec

106 %/sec

When administering a dose of 90 mg/kg prepared from Chlorpyrifos and Cypermethrin pesticide, 3730 instances of biological harm occur in every second for a laboratory animal with a body weight of approximately 26.84 gm. Likewise, the same dose causes 10,600 instances of harm per second for a laboratory animal with a body weight of approximately 28.24 gm. This means the same doses can still manifest gross biological responses on a study animal with a body mass of up to 10.01 kg and 29.9 kg respectively, which can be calculated using this formula,. ( ).The severity of the toxic reaction caused by the administered dose can help determine the maximum effective dose for the body weight of the treated study animal, and this information is valuable in the development of pharmaceutical products. A test chemical with a computed toxic severity and toxic reaction rate less than zero provided it is proven to be non-genotoxic or non-cytotoxic, could be considered in the development of therapeutic agents. It's important to evaluate the toxic severity and toxic reaction rate of a dose over an adequate period, such as once every five days, to validate the safety of the test chemical for health.

).The severity of the toxic reaction caused by the administered dose can help determine the maximum effective dose for the body weight of the treated study animal, and this information is valuable in the development of pharmaceutical products. A test chemical with a computed toxic severity and toxic reaction rate less than zero provided it is proven to be non-genotoxic or non-cytotoxic, could be considered in the development of therapeutic agents. It's important to evaluate the toxic severity and toxic reaction rate of a dose over an adequate period, such as once every five days, to validate the safety of the test chemical for health.

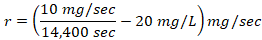

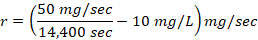

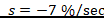

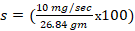

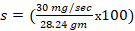

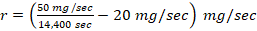

The toxic reaction rate of a dose

The toxic reaction rate refers to the amount of a test drug that has caused adverse biological effects in study animals at the organismal level. It represents the approximate amount of the administered test chemical that has reached the drug receptor or biological target and caused gross adverse biological response, expressed in milligram per second (mg/sec). This can also be quantitatively expressed using an integrated biological approach with the mathematical equation mentioned in formula 2 earlier. The administered doses prepared from Dichlorvos and Chlorpyrifos at 10 and 50 mg/kg caused a toxic reaction rate that was less than zero (Table 6). The toxic reaction rate of Dichlorvos and Chlorpyrifos administered to lab Balb c mice at a dose of 10 and 50 mg/kg shown in Table 6 was computed as follows:

1. The toxic reaction rate of a dose at 10 and 50 mg/kg prepared from Dichlorvos test chemical.

= -19.9 mg/sec

= -9.9 mg/sec

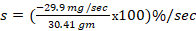

2. The toxic reaction rate of a dose at 10 and 50 mg/kg prepared from Chlorpyrifos test chemical.

, r= -29.9 mg/sec

, r= -29.9 mg/sec

,r= -19.9 mg/sec.

,r= -19.9 mg/sec.

The toxic reaction rate of doses at 10 and 50 mg/kg, prepared from each test chemical, was calculated to be less than zero. This suggests that a negligible amount of the drug reached the drug receptor or biological target. It appears that each dose boosted the immune response, which countered the toxic reaction rate of the tested dose (Table 6). Further investigation is needed to determine the appropriate length of time in which the toxic reaction rate should be calculated to validate the data adequately.

When administered at a dose of 90 mg/kg, prepared from Chlorpyrifos and Cypermethrin, the test chemicals caused toxic reaction rates of 10 mg/sec and 30 mg/sec respectively (Table 6). This implies that of the administered doses at 90 mg/kg from both test chemicals, 11.1% and 33.3% reached the vicinity of the drug receptor or biological target, eliciting significant biological responses in treated Balb c mice. This also suggests that Cypermethrin is more toxic than Chlorpyrifos.

Conclusions

The toxic properties of test chemicals are diverse, with a variety of adverse effects, making preclinical trials challenging to monitor and evaluate. A chemical that is safe for the liver may be toxic to the kidneys, and a substance that is safe for the respiratory system may be harmful to the digestive system. No matter which tissue, organ, or organ system is affected by the administered test chemicals, the adverse effect is directly manifested in the immune system of the treated study animals. A holistic biological approach is necessary to analyze this in a harmonized manner, considering the administered dose, the duration in which signs and symptoms of toxicity manifest in treated animals, and changes in the concentration of immunoglobulins in blood serum.

References

- 1.Belay Y. (2011) Study of safety and effectiveness of traditional dosage forms of the seed of Aristolochiaelegansmast against malaria and laboratory investigation of pharmaco-toxicological properties and chemical constituents of its crude extracts, Ann Trop Med Public Health. 4, 33-41.

- 2.Belay Y. (2019) Study of the principles in the first phase of experimental pharmacology: The basic step with assumption hypothesis, BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 30, 10-1186.

- 3.Belay Y, The. (2019) Dose and its Acute Toxicology: A Systematic Review Article in the First Phase of Experimental Pharmacology. , J Comp Biol Sys 2-1.

- 4.J H McGee, D J Erikson, Galbreath C, D A Willigan, R D Sofia. (1998) Acute, Sub chronic, and chronic Toxicity Studies with Felbamate, 2-Phenyl-1,3-propanediol Dicarbamate, Toxicological Sciences. 45-225.

- 5.Chapman Kathryn, Sally Robinson NC3RS. (2007) Astrazeneca, Challenging the regulatory requirement for acute toxicity studies in the development of new medicine, A workshop report.

- 6.Belay Y T. (2019) Parameters for Grading the Toxic Severity of Test Chemicals: A Review Article. in the Advancement of Unknown Drugs into the Clinic. AdvNanomedNanotechnol Res 1(2), 43-52.

- 7.Chapman Kathryn, Robinson Sally. (2007) Astrazeneca, Challenging the regulatory requirement for acute toxicity studies in the development of new medicines. Toxicology. 172-2.

- 8.Chinedu E, Arome D, Solomen F. (2013) A new method for determining acutetoxicity in animal models. Toxicol Int. 20(3), 224-6.

- 10.Belay Y T. (2019) Misconception about the role of a dose in pharmacology: Short review report on the biological and clinical effects. , AdvBioeng Biomed Sci Res, Vol 2(3), 2640-4133.

- 11.Harry W Schroeder, Cavacini Lisa. (2013) Structure and function of the immunoglobulins. , J Allergy ClinImmunol 125-202.

- 12.Fritz H Kayser. (2005) Medical Microbiology; Basic principles of Immunology, Translation of the 10th German edition. 43-132.

- 13.Bertram G Katzung. (2011) Basic and Clinical pharmacology; Elements of the immune system, 12th edition. 977-998.

- 14.Robert K Murray. (2003) Harber’s illustrated Biochemistry; Overview of Metabolism. 26th edition 131-138.

- 16.D A Levison, Reid R, Burt A D, Harrison D J, Fleming S. (2008) Muir’s Textbook of Pathology. Clinical genetics,cell injury, inflammation and repair. 14th Edn. Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd. 30-77.

- 17.James M Ritter, Lionel D Lewis. (2008) Timothy GK Mant and Albert Ferro. A Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Adverse Drug Reaction, Hodder Arnold, 5thEdition 73-82.