Toward Better Care for Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria: A Review of Challenges and Interventions

Abstract

With more than 150,000 affected infants annually, Nigeria bears the largest burden worldwide of sickle cell disease (SCD), making it a significant public health concern. The management of SCD in Nigeria is challenging, despite advancements in medical research and increased knowledge. This review examines the numerous issues surrounding SCD in the nation, including the financial burden on affected families, the lack of specialized care facilities, the absence of newborn screening programs, the sociocultural stigmatization of SCD, and restricted access to high-quality healthcare. Additionally, inadequate public health education and a lack of coordinated national policies result in delayed diagnosis and suboptimal treatment outcomes. We also highlighted recent efforts and recommendations aimed at improving early detection, comprehensive care, and community support. Addressing these challenges through expanded health education and enhanced healthcare infrastructure is essential to reducing morbidity and mortality associated with SCD in Nigeria.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Anubha Bajaj, Consultant Histopathologist, A.B. Diagnostics, Delhi, India

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Grace Valentine Olagunju, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Citation:

Introduction

One of the two aberrant hemoglobin genes that are inherited is the hemoglobin "S" variant and it results in the genetic blood condition sickle cell disease (SCD). Individuals who inherit a defective gene from both parents are likely to show it; it is passed in an autosomal recessive pattern¹. The condition of homozygosity (HbSS) is known as sickle cell anemia (SCA), hemoglobin SC disorders, sickle beta-plus thalassemia, and sickle beta-zero thalassemia, the latter of which has a clinical severity comparable to HbSS are additional clinically significant genotypes.

Although SCD is a global health concern, It is more common in people of African heritage and is believed to have originated in Sub-Saharan Africa2. Nigeria, in particular, bears the highest burden of the disease worldwide, accounting for a significant proportion of affected births annually 3. Worldwide, SCD affects around 300,000 infants annually, and by 2050, that figure is expected to increase to 400,0002,4. In sub-Saharan Africa, where access to specialized medical care and efficient public health initiatives is still uneven and frequently insufficient, the disease continues to be a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality 5.

Despite Nigeria bearing one of the highest global burdens of SCD, its healthcare system remains inadequately equipped to address the disease comprehensively. Many general practitioners encounter SCD cases infrequently and do not have access to current clinical proposals, diagnostic equipment, and facilities for specialist care. These gaps contribute to delayed diagnoses, inadequate disease management, and poor health outcomes. This study thoroughly examines the primary barriers to SCD early detection, treatment, and prevention in Nigeria and suggests effective strategies to enhance health outcomes for impacted communities.

Disease Burden in Nigeria Currently

Nigeria harbors the highest prevalence globally, with approximately 40 million individuals carrying the sickle cell gene6. According to current estimates, 150,000 babies are born each year with SCD, representing approximately 33% of the global burden. The mortality rate among children due to SCD is high, with over 100,000 neonatal deaths each year attributed to the disease2, 6, 7. SCD prevalence varies across states in Nigeria, ranging from 1% to 3%. Also, a comprehensive retrospective analysis carried out by Gomez et al. 8 in South-South, Benin, Nigeria, shows an SCD prevalence of 3% and while the carrier rate is approximately 22% confirming the statistics of SCD across states in Nigeria. However, Hemoglobin S (HbS) is relatively evenly distributed across Nigeria, while hemoglobin C (HbC) is more concentrated in the western regions and declines progressively towards the east 9.

A Genetics Overview of SCD

Sickle hemoglobin (HbS), an aberrant form of hemoglobin, is produced in SCD as a result of a particular genetic mutation. The sixth codon of the β-globin gene changes from GAG to GTG due to a single nucleotide substitution in this mutation10.Thymine takes the place of adenine. At position six of the hemoglobin beta chain, valine therefore functions in place of glutamic acid. This seemingly minor alteration significantly affects the physical and chemical properties of hemoglobin, reducing its solubility and stability11In Nigeria, the classifications of SCD are based on the specific hemoglobin genotype. The most common classifications are :

Hemoglobin SS disease or Sickle Cell Anemia: This is the most severe form of SCD, currently characterized by frequent and intense pain crises with higher complications12.

Hemoglobin SC disease: More prevalent in the southwestern part of Nigeria13. HbSC disease individuals have pain crises and potential organ complications, but milder than in the HbSS genotype.

Hemoglobin Sβ+ (beta) thalassemia: This condition causes a reduction in the synthesis of beta-globin, resulting in smaller-than-normal red blood cells (microcytosis)14. This results in milder symptoms compared to the HbSS too.

Hemoglobin Sβ0 (Beta-zero) thalassemia: Also similar to other types, it is caused by a mutation in the beta-globin gene; however, the damaged gene does not produce any beta-globin at all. It produces clinical symptoms that closely resemble those of hemoglobin SS (HbSS) disease15. In some cases, the symptoms may be even more severe, with increased risk of complications and a poorer overall prognosis.

Hemoglobin SD, hemoglobin SE, and hemoglobin SO: These less common kinds of SCD are linked to less severe consequences and milder symptoms16.

Sickle Cell Trait (SCT): Individuals with SCT inherit one normal hemoglobin gene (HbA) and one sickle hemoglobin gene (HbS) from the parents17. While SCT is generally asymptomatic and individuals typically lead normal lives, HbS gene can be passed to their children. Although rare, certain health complications such as exertional rhabdomyolysis, hematuria, and splenic infarction under extreme conditions have been associated with sickle cell trait18.

Genetic Inheritance Pattern

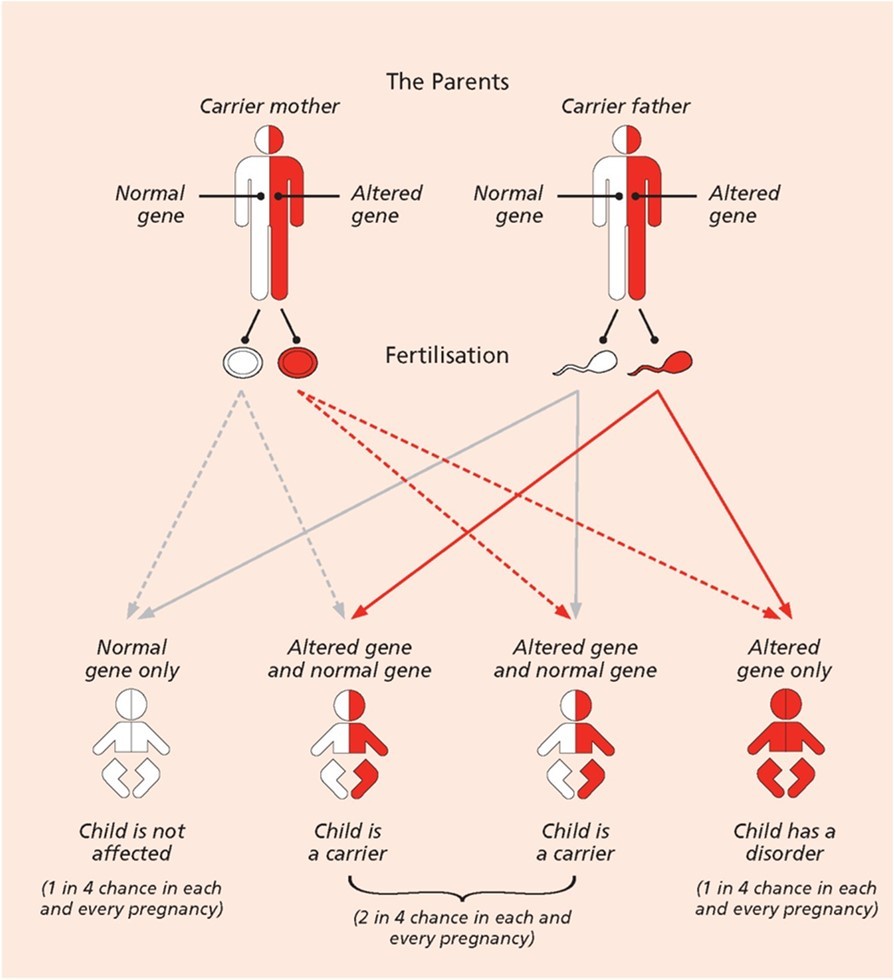

SCD is a genetic blood condition that has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern that affects both males and females equally19, implying that the disease can only manifest in a person who inherits two copies of the defective gene, one from each parent. The beta- globin subunit of hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen throughout the body, is encoded by the HBB gene, which has a genetic mutation that causes SCD. The amino acid glutamic acid is specifically replaced with valine at the sixth position of the beta-globin chain due to a single nucleotide substitution in this mutation. Due to this minor but important alteration, hemoglobin S (HbS), which differs from normal hemoglobin A (HbA) in its physical characteristics, is produced 20.

Hemoglobin S molecules attach to one another and create long, stiff structures inside red blood cells when oxygen levels are low21. These formations reduce the cells' flexibility and capacity to flow through tiny blood arteries by deforming them into a distinctive sickle or crescent shape. Sickled cells can thereby block blood flow, resulting in discomfort, damage to organs, and other issues. Chronic anemia can also result from these malformed cells' propensity to degrade too soon19, 20, 21.

The sickle cell trait (AS genotype) is a condition in which a person inherits one normal hemoglobin gene (HbA) and one sickle cell gene (HbS). People with this trait are generally healthy and do not exhibit symptoms of SCD, but they are carriers of the disease. However, the mutant gene can be passed on to their offspring. A child born to two sickle cell trait carriers has a 25% chance of inheriting two normal genes (HbA/HbA) and not affected, a 50% chance of inheriting one normal and one sickle gene (HbA/HbS) and also being a carrier, and a 25% chance of inheriting two sickle genes (HbS/HbS) and developing sickle cell disease. It is also possible for SCD to arise from inheriting one HbS gene and another abnormal hemoglobin gene. These variant forms of sickle cell disease include combinations such as hemoglobin SC disease (HbSC) and sickle beta- thalassemia (HbS/β-thal)22. In these cases, the individual has one HbS gene and a different mutation affecting the beta-globin gene, resulting in disease manifestations that may be similar to or milder than sickle cell anemia, depending on the specific genetic combination. By understanding the inheritance pattern and molecular basis of SCD, individuals and healthcare providers can make informed decisions regarding family planning, early diagnosis, and treatment options 11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Diagram to show a pattern of genetic inheritance for SCD (Source: Sickle Cell Foundation of Minnesota, 2025).

Common complications and clinical features

Around five months of age, symptoms surface. The disease varies from person to person and changes over time. Among the symptoms and signs of SCD listed by Medline in 2024 are:

Anemia: Anemia is caused by a low level of red blood cells as a result of sickle cell breakdown and premature death.

Fatigue: Insufficient red blood cells reduce the body’s oxygen-carrying capacity, causing fatigue and other complications.

Pain episodes: When sickle-shaped red blood cells block blood flow through tiny blood capillaries, especially in the joints, chest, and abdomen, sickle cell disease pain results. Another typical symptom is bone pain. Complications include leg ulcers, bone and joint degeneration, and other long-term tissue damage can cause persistent pain in certain adults and adolescents with sickle cell anemia.

Hand and foot swelling: The cause of the edema is sickle-shaped red blood cells that block blood flow to the hands and feet.

Chronic infections: Damage to the spleen from sickle cell disease may make patients more prone to infections. Infants and children with sickle cell anemia are routinely given vaccinations and medications to help prevent potentially deadly diseases like pneumonia.

Puberty or delayed growth: Red blood cells give the body the oxygen and nutrition it needs to survive. Teenagers' puberty and infants' growth can be delayed by a lack of healthy red blood cells.

Visual issues: The small blood vessels that supply the eyes can get blocked by sickle cells. Damage to the retina, which is in charge of processing visual images, can cause vision problems.

Challenges with SCD

The term "crisis" is frequently used to describe sickle cell challenges. Among them are:

Vaso-occlusive Crisis (VOC): VOC is a painful episode caused by sickled red blood cells sticking to blood vessel walls, which blocks blood flow. It leads to tissue ischemia and infarction, resulting in severe pain. VOC is a hallmark complication of SCD requiring prompt treatment23.Most people with SCD experience discomfort by the time they are six years old. Pain typically affects the back, chest, and extremities, but it can come from anywhere in the body. Some patients may experience both a vaso-occlusive crisis and a fever 24.

Splenic Sequestration Crisis: Spleen infarction commonly occurs in individuals with SCD during early childhood. Because of its tiny blood arteries and vital function in the lymphoreticular system, the spleen is especially susceptible. In a splenic sequestration crisis, sickled red blood cells become trapped in the spleen, leading to sudden and painful splenic enlargement. Hemoglobin levels can drop rapidly, and patients are at risk of hypovolemic shock. If not promptly recognized and treated, this condition can be life- threatening25.

Aplastic Crisis: With reticulocytopenia and rapidly declining hemoglobin levels, sickle cell disease presents as sudden weakness and pallor. An aplastic crisis is typically triggered by parvovirus B19, which directly impairs bone marrow function, leading to decreased production of red blood cells. However, other viral infections may also play a role. In SCD, the patient's baseline anemia worsens due to the shortened lifespan of red blood cells, which can fall to dangerously low levels. Typically lasting seven to ten days, the condition is self-limiting26.

Acute Chest Syndrome (ACS): Hypoxia caused by chest hypoventilation during a VOC crisis is often the etiology of ACS. It may also occur due to a fat embolism originating from the distal bone during the VOC. When sickled erythrocytes attach to the pulmonary microvasculature due to hypoxia, the lungs experience local hypoxia, which in turn causes more RBCs to sickle, creating a vicious cycle. Symptoms and signs include fever, cough, tachypnea, chest discomfort, hypoxia, wheezing, respiratory distress, and even heart failure. Abnormal lung findings and pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiography should trigger suspicion of acute chest syndrome because poor surveillance and delayed treatment might result in fast respiratory failure and higher mortality27.

Hemolytic Crisis: This crisis is identified by an abrupt decrease in hemoglobin levels. Patients with coexisting G6PD deficiency frequently experience it 27.

Diagnosis of SCD

The diagnosis of SCD involves a combination of screening methods, confirmatory laboratory tests, and clinical evaluation. In many countries, newborns are routinely screened for SCD through a blood test obtained via heel prick, which is analyzed using techniques such as isoelectric focusing (IEF)28, High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)29,or DNA-based methods to detect abnormal hemoglobin variants. If initial screening indicates the presence of hemoglobin S or other variants, confirmatory testing is done using hemoglobin electrophoresis, which is considered the gold standard 30, 31. This test identifies specific types of hemoglobin, helping distinguish between SCD and SCT. Genetic testing can also be performed to detect mutations in the HBB gene responsible for SCD, particularly in cases where the results are inconclusive or for prenatal diagnosis. Clinically, people with untreated SCD may exhibit symptoms include persistent anemia, frequent episodes of discomfort (vaso-occlusive crises), hand and foot edema, heightened vulnerability to infections, slowed growth, and visual issues. Additional blood tests that show signs of hemolysis and sickled red blood cells, such as the complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, bilirubin levels, and peripheral blood smear examination, can confirm the diagnosis. The sickle cell gene can be found in the fetus through prenatal diagnosis using amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling in high- risk pregnancies. Early diagnosis is critical for timely intervention and management to prevent complications associated with the disease.

Current Management of SCD in Nigeria

In Nigeria, current treatments for SCD include hydroxyurea32, folic acid supplements33, analgesics for pain management34, Antibiotics for infections35, and occasional blood transfusions for severe cases36. Preventive measures such as vaccinations and routine monitoring are recommended, but are not consistently implemented37, 38. While bone marrow transplant offers a potential cure, it remains largely inaccessible due to high costs and limited facilities39. Access to treatment is impeded by inadequate healthcare infrastructure, a lack of available specialists, and financial constraints, leading many patients to depend on traditional remedies despite their unproven efficacy.

Barriers to Effective Management of SCD in Nigeria

Healthcare System Challenges

Adigwe in his study in 2023 1found that respondents perceived the facilities and equipment for managing SCD in Nigeria as inadequate. Barriers to timely and effective care include institutional delays, limited specialist centers, negative provider attitudes, and poor patient-provider communication. Broader systemic challenges highlighted by Bucher et al. 40 include weak government commitment, poor infrastructure, lack of affordable care, absence of local bone marrow registries and specialized diagnostic labs, and unreliable electricity supply.

Economic Barriers

High costs of outpatient care, expensive medications, and inadequate health insurance limit access to quality treatment for sickle cell disease. Families without insurance often experience fragmented care and delays. Regular checkups, medications like hydroxyurea, and crisis management are costly 41, 42 while widespread economic hardship restricts access to proper healthcare and nutrition essential for managing SCD.

Policy and Infrastructure Gap

Although Nigeria has policies targeting non-communicable diseases, implementation and monitoring are poor. Early diagnosis is rare, and many children with SCD are not diagnosed until severe symptoms emerge. Planning successful initiatives and allocating resources is challenging when there is a lack of national data. For the best care, SCD newborns who are identified during pregnancy or during newborn screening should ideally be sent to comprehensive SCD clinics. On the other hand, delayed diagnosis is still linked to SCD in Nigeria 43. There is still a lack of public health awareness regarding SCD in Nigeria, according to recent surveys 44. As of present day, there are no coordinated national measures to control SCD, even though Nigeria is the most populated black country on the planet with the biggest burden of the illness. According to current data, Nigerian SCD patients continue to receive subpar care 45.

Sociocultural Factors

People with SCD may be seen as weak or cursed, leading to social exclusion and reluctance to seek help. Beliefs in spiritual causes or traditional medicine can delay proper medical intervention. Lack of awareness or disregard for genotype compatibility in relationships increases the risk of having children with SCD46.

Educational and Awareness Barriers

Access to Medications and Technology

Essential drugs like hydroxyurea are not always available or affordable in local pharmacies. Many healthcare centers lack the equipment to diagnose or monitor SCD properly. Curative treatment options like stem cell transplant are inaccessible for most due to cost and availability. In developing countries like Nigeria, secondary control techniques like continuous transfusion therapy and hydroxyurea use encounter unique difficulties49. These difficulties include the inaccessibility of blood and blood components, the requirement that patients and family members routinely find blood and blood donors, the expense of iron chelation, the possibility of infections that might be contracted during transfusions, and the total cost of chronic blood transfusions50. A new study claims that the mean annual expense of hyper transfusion for children with SCD in Ibadan was 3,276 USA dollars (SD = 1,168). Additionally, using metal chelators to address iron overload,a potentially unavoidable side effect of long-term transfusion, raises costs. Additionally, HSCT, the sole potentially effective disease-modifying treatment for SCD, is presently accessible in Nigeria and has been documented51.

Current Interventions in the Management of SCD in Nigeria

Government and NGO Initiatives

In recent years, various government bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have taken steps to improve SCD care and support services in Nigeria 52. The Federal Ministry of Health has endorsed the integration of SCD control into national health policies, and some states have launched pilot newborn screening programs. NGOs such as the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria (SCFN) have played a pivotal role in offering diagnostic services, patient counseling, and public education 53. Despite these efforts, there is still a need for more widespread implementation and coordination of these programs to achieve national impact 50.

Community Awareness Programs

Awareness campaigns targeting schools, religious institutions, and community groups are gaining momentum, with the aim of reducing stigma and promoting early diagnosis and genotype testing. These initiatives often focus on educating the public about the inheritance pattern of SCD, the importance of premarital screening, and the need for timely medical care. However, challenges such as misinformation, cultural beliefs, and limited access to education in rural areas hinder the effectiveness of these campaigns54.

Advances in Genetic Counseling and Education

Genetic counseling is increasingly recognized as a vital tool in preventing the transmission of SCD. Some tertiary health institutions now offer genetic counseling services as part of reproductive health care. In addition, public education efforts are helping to improve understanding of genotype compatibility among couples planning to marry. Expanding access to trained counselors and integrating genetic education into school curricula are crucial next steps55.

Role of Partnerships and International Support

Collaborations with international organizations and academic institutions have supported the development of screening programs, training of healthcare workers, and research on SCD in Nigeria. Partnerships with entities such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Society of Hematology (ASH), and international donors have contributed technical expertise, funding, and strategic planning support56. These collaborations are instrumental in building capacity and sustaining long-term interventions

Research and Data Collection Priorities

There is a growing emphasis on strengthening research and data collection to inform policy and improve clinical outcomes. Institutions like the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) and select teaching hospitals are conducting studies on disease prevalence, treatment outcomes, and barriers to care. Nonetheless, research efforts are often hampered by limited funding, lack of infrastructure, and poor data management systems1. Prioritizing investment in national registries, population-based studies, and implementation research is essential to advancing SCD control strategies.

Suggested Solutions to SCD Management in Nigeria

To improve outcomes for individuals living with SCD in Nigeria, several strategic interventions are essential. First, expanding newborn screening programs nationwide would enable early detection and prompt initiation of care, which significantly reduces childhood mortality and long-term complications. Public education and advocacy must also be intensified, especially around genotype screening, to promote informed reproductive choices and reduce the incidence of the disease. Integrating SCD services into primary health care would ensure that basic diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care are accessible at the community level, particularly in rural and underserved areas. Additionally, introducing subsidies or health insurance coverage for the chronic management of SCD including medications like hydroxyurea, routine monitoring, and hospital visits would alleviate the financial burden on families and improve treatment adherence. Finally, collaborating with international agencies can bring in vital funding, technical expertise, and capacity-building initiatives to strengthen Nigeria’s healthcare system and support the sustainable management of SCD.

Conclusion

Nigeria's newborn screening program is not examined on a regional or national level, despite the country's high SCD burden. There are currently no complete specialist centers in Nigeria that have the necessary multidisciplinary teams to care for individuals with sickle cell disease. Nonetheless, sickle cell disease is a chronic illness, and while it may not be possible to eliminate its problems, leading a healthy lifestyle can help to mitigate some of them. Therefore, we must make every effort to educate individuals of all ages. The disease known as sickle cell disease is complicated. Some of these issues can be avoided with high-quality medical care from physicians and nurses who are well-versed in the disease. The best choice is a hematologist, a doctor who focuses on blood problems and collaborates with a team of specialists. It will be very beneficial if medical personnel who treat sickle cell disease receive ongoing training. The patients' and their parents' or caregivers' education should be the focus of future initiatives. Finally, to maximize their knowledge and abilities in sickle cell disease care, health caregivers should continuously take professional refresher and update courses.

Funding

None

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, G.V.O.; writing—original draft preparation, G.V.O., A.T.A, and S.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.V.O., S.Z., and V.A.O.; supervision, S.Z. and V.A.O. All authors made substantial contributions to the work and as well approved the final version for publication.

References

- 1.O P Adigwe, Onavbavba G, S O Onoja. (2023) Impact of Sickle Cell Disease on Affected Individuals in Nigeria: A Critical Review. , Int J Gen Med 1-3503.

- 2.O C Nwabuko, Onwuchekwa U, Iheji O. (2022) An Overview of Sickle Cell Disease from the Socio-Demographic Triangle - a Nigerian Single-Institution Retrospective Study. Pan Afr Med J. 41-161.

- 3.Galadanci N, B J Wudil, T M Balogun, G O Ogunrinde, Akinsulie A et al. (2014) Current Sickle Cell Disease Management Practices in Nigeria. Int Health. 1, 23-28.

- 4.Odame I. (2014) Perspective: We Need a Global Solution. (7526), S10–S10. https://doi.org/10.1038/515S10a , Nature 515.

- 5.F B Piel, T N Williams. (2017) . , Subphenotypes of Sickle Cell Disease in Africa. Blood 130(20), 2157-2158.

- 6.I, L A Ali, C, Jasseh M, Zentar M et al. (2024) . Socio- Economic Burden of Sickle Cell Disease on Families Attending Sickle Cell Clinic in Kano State, Northwestern Nigeria. Global Pediatrics, S 100193-10.

- 7.O E Nnodu, A P Oron, Sopekan A, G O Akaba, F B Piel et al. (2021) . Child Mortality from Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria: A Model-Estimated, Population-Level Analysis of Data from the 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. The Lancet Haematology 8(10), 10-1016.

- 8.Gomez S, Amoussa A E R, Dedjinou E, Kakpo M, Gbédji P et al. (2024) . Epidemiologic Profile of Hemoglobinopathies in Benin. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy 4c, S257–S262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.htct.2024.07.008 .

- 9.Go E, Nb O, Ml O, Ki A. (2017) . Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria A Review. IOSR JDMS, 1c (01) 87-94.

- 10.Inusa B P D, L, Kohli N, Patel A, Ominu-Evbota K et al.Sickle Cell Disease-Genetics, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatment. , Int J Neonatal Screen 5(2), 20-10.

- 11.S H Lim, Fast L, Morris A. (2016) Sickle Cell Vaso-Occlusive Crisis: It’s a Gut Feeling. , J Transl Med 14(1), 334-10.

- 12.Akaba K, Nwogoh B, Obanife H, Essien O, Epoke E. (2020) . Prevalence of Chronic Complications in Adult Sickle Cell Anemia Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in South-South , Nigeria. Niger 2, 665-10.

- 13.Faremi F, B A Onitiju, O E, Olatubi M. (2023) Clients’ Satisfaction with Pain Managementby Healthcare Providers during Sickle Cell Crisisin Selected Health Facilities in Ogun State Nigeria –a Cross Sectional Study. ppiel. 31(3), 140-147.

- 14.M A Engle, K H Ehlers, J E O’Loughlin, Giardina P, Hilgartner M. (1987) Hematologic Disease. In The Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease;. , US: Boston, MA 319-338.

- 15.Figueiredo S. (2015) The Compound State: Hb S/Beta-Thalassemia. , Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 37(3), 150-152.

- 16.Tauseef U, Anjum M, Ibrahim M, H S Baqai, Tauseef A et al. (2021) . , OCCURRENCE OF UNUSUAL HAEMOGLOBINOPATHIES IN BALOCHISTAN: HB SD AND HB SE - PRESENTATION WITH OSTEOMYELITIS. Rev Paul Pediatr 3, 0462-2021.

- 17.T S Brown, Lakra R, Master S, Ramadas P. (2023) Sickle Cell Trait: Is It Always Benign?. , J Hematol 12(3), 123-127.

- 18.Tantawy A A G. (2014) The Scope of Clinical Morbidity in Sickle Cell Trait. , Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 15(4), 319-326.

- 19.Inusa B, Hsu L, Kohli N, Patel A, Ominu-Evbota K et al.. Sickle Cell Disease—Genetics, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation and Treatment. IJNS 201G 5(2), 20-10.

- 21.E R Henry, Cellmer T, E B Dunkelberger, Metaferia B, Hofrichter J et al. (2020) Allosteric Control of Hemoglobin S Fiber Formation by Oxygen and Its Relation to the Pathophysiology of Sickle Cell Disease. , Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117(26), 15018-15027.

- 22.Guarda Da, C, Yahouédéhou S C M A, R P Santiago, Neres J S D S et al. (2020) Sickle Cell Disease: A Distinction of Two Most Frequent Genotypes (HbSS and HbSC). PLoS ONE. 15(1), 0228399-10.

- 23.Jang T, Poplawska M, Cimpeanu E, Mo G, Dutta D et al. (2021) Vaso-Occlusive Crisis in Sickle Cell Disease: A Vicious Cycle of Secondary Events. , J Transl Med 1, 397-10.

- 24.C T Quinn, N J Lee, E P Shull, Ahmad N, Z R Rogers et al. (2008) . Prediction of Adverse Outcomes in Children with Sickle Cell Anemia: A Study of the Dallas Newborn Cohort. Blood 111(2), 544-548.

- 25.R W Powell, G L Levine, Y M, V N Mankad.Acute Splenic Sequestration Crisis in Sickle Cell Disease: Early Detection and Treatment. , J Pediatr Surg 27(2), 215-218.

- 26.S T Chou, R M Fasano. (2016) Management of Patients with Sickle Cell Disease Using Transfusion Therapy. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 30(3), 591-608.

- 27.Simon E, Long B, Koyfman A. (2016) Emergency Medicine Management of Sickle Cell Disease Complications: An Evidence-Based Update. , J Emerg Med 51(4), 370-381.

- 28.N S Green, Zapfel A, O E Nnodu, Franklin P, V N Tubman et al. (2022) The Consortium on Newborn Screening in Africa for Sickle Cell Disease: Study Rationale and Methodology. Blood Adv. , c 24, 6187-6197.

- 29.Frömmel C. (2018) Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease and Other Hemoglobinopathies: A Short Review on Classical Laboratory Methods-Isoelectric Focusing, HPLC, and Capillary Electrophoresis. , Int J Neonatal Screen 4(4), 10-3390.

- 30.Elendu C, D C Amaechi, C E Alakwe-Ojimba, T C Elendu, R C Elendu et al. (2023) Understanding Sickle Cell Disease: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options. Medicine (Baltimore). 102(38), 35237-10.

- 31.Nigam R, Sharda B, A V Varma. (2024) . Comparative Study of Sickling Test, Solubility Test, and Hemoglobin Electrophoresis in Sickle Cell Anemia. MGMJ 11(1), 31-37.

- 32.Osunkwo I, Manwani D, Kanter J. (2020) Current and Novel Therapies for the Prevention of Vaso-Occlusive Crisis in Sickle Cell Disease. Ther Adv Hematol. 11, 2040620720955000-10.

- 33.Agbor Arrey, B D, Panday P, Ejaz S, Gurugubelli S et al. (2024) Folic Acid in the Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.57962

- 34.Okpala I, Tawil A. (2002) Management of Pain in Sickle-Cell Disease. , J R Soc Med 5(9), 456-458.

- 35.F J Olusesan, O, O E, O I, A O Tolulope. (2017) Prescription Audit in a Paediatric Sickle Cell Clinic in South-West Nigeria: A Cross- Sectional Retrospective Study. Malawi Med J. 2, 285-289.

- 36.A S. (2015) Management of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review for Physician Education in Nigeria (Sub-Saharan Africa). Anemia. 1-21.

- 37.A S. (2015) Management of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review for Physician Education in Nigeria (Sub-Saharan Africa). Anemia. 1-21.

- 38.O, A I Otaigbe, Ibidapo M O O. (2005) Outcome of Holistic Care in Nigerian Patients with Sickle Cell Anaemia. Clin Lab Haematol. 27(3), 195-199.

- 39.H W Musuka, P G Iradukunda, Mano O, Saramba E, Gashema P et al. (2024) Evolving Landscape of Sickle Cell Anemia Management in Africa: A Critical Review. TropicalMed. 12-292.

- 40.Bucher C. (2014) First Successful Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for a Sickle Cell Disease Patient in a Low Resource Country (Nigeria): A Case Report. Ann Transplant. 1-210.

- 41.Olatunya O, Ogundare O, Fadare J, Oluwayemi O, Agaja O et al. (2015) . The Financial Burden of Sickle Cell Disease on Households in Ekiti, Southwest Nigeria. CEOR 545-10.

- 42.Adegoke S, Abioye-Kuteyi E, Orji E. (2014) The Rate and Cost of Hospitalisation in Children with Sickle Cell Anaemia and Its Implications in a Developing Economy. Afr. 14(2), 475-10.

- 43.Akodu S, Diaku-Akinwumi I, Njokanma O.Age at Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Anaemia in. , Lagos, Nigeria, Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 5(1), 2013001-10.

- 44.Fa O, Ka O. (2012) Effects of Health Education on Knowledge and Attitude of Youth Corps Members to Sickle Cell Disease and Its Screening in Lagos State. , J Community Med Health Edu 10-4172.

- 45.Galadanci N, B J Wudil, T M Balogun, G O Ogunrinde, Akinsulie A et al. (2014) Current Sickle Cell Disease Management Practices in Nigeria. International Health. 1, 23-28.

- 46.T O Rosanwo, L S Kean, N M Archer. (2021) End the Pain: Start with Antiracism. , American J Hematol 1, 4-6.

- 47.O U Ezenwosu, B F Chukwu, A N Ikefuna, A T Hunt, Keane J et al. (2015) . Knowledge and Awareness of Personal Sickle Cell Genotype among Parents of Children with Sickle Cell Disease in Southeast Nigeria. J Community Genet 4, 369-374.

- 48.O A Babalola, C S, B J, J F Cursio, A G Falusi et al.Knowledge and Health Beliefs Assessment of Sickle Cell Disease as a Prelude to Neonatal Screening in Ibadan. , Nigeria. Journal of Global Health Reports 201, 2019062-10.

- 49.A S, J C Obieche. (2014) Hypertransfusion Therapy. in Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria. Advances in Hematology 1-8.

- 50.I A Lagunju. (2013) Complementary and Alternative Medicines Use in Children with Epilepsy in. , Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 42(1), 15-23.

- 51.Emmanuelchide O, Charle O, Uchenna O. (2011) . Hematological Parameters in Association with Outcomes in Sickle Cell Anemia Patients0. Indian J Med Sci, c5 (9) 393-10.

- 52.Isa H, Okocha E, S A Adegoke, Nnebe-Agumadu U, Kuliya-Gwarzo A et al. (2023) Strategies to Improve Healthcare Services for Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria: The Perspectives of Stakeholders. Front Genet. 14, 1052444-10.

- 53.Akinsete A.Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease in Sub-Saharan Africa: We Have Come a Long Way, but Still Have Far to Go. , J Global Med 2(1), 79-10.

- 54.McCormick M, H A Osei-Anto, R M Martinez. (2020) Committee on Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action;. , Washington, D.C 25632-10.